In celebration of black history Month, we are reprinting portions of an article from our newsletter # 28 dated Fall 2001. It is as relevant today as it was 15 years ago. For the complete article see https://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/articles/bc_or_race_control.php.

“Birth Control or Race Control? Sanger and the Negro Project”

The Negro Project, instigated in 1939 by Margaret Sanger, was one of the first major undertakings of the new Birth Control Federation of America (BCFA), the product of a merger between the American Birth Control League and Sanger’s Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau, and one of the more controversial campaigns of the birth control movement. Developed by white birth control reformers, who consulted with African-Americans for help in promoting the project only well after its inception, the Negro Project and associated campaigns were, nevertheless, widely supported by such black leaders as Mary McLeod Bethune, W. E. B. DuBois, and Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Influenced strongly by both the eugenics movement and the progressive welfare programs of the New Deal era, the Negro Project was, from the start, largely indifferent to the needs of the black community and constructed in terms and with perceptions that today smack of racism.

Life Magazine, May 6, 1940, p.66

What it became was not the project Sanger had first envisioned. As she wrote in an initial fund-raising request to Albert Lasker, the wealthy advertising executive just beginning his post-business career in medical philanthropy, she simply hoped to help “a group notoriously underprivileged and handicapped to a large measure by a ‘caste’ system that operates as an added weight upon their efforts to get a fair share of the better things in life. To give them the means of helping themselves is perhaps the richest gift of all. We believe birth control knowledge brought to this group, is the most direct, constructive aid that can be given them to improve their immediate situation.” Sanger viewed the Negro Project as another effort to help African-Americans gain better access to safe contraception and maintain birth control services in their community as she had attempted to do in Harlem a decade earlier when Sanger’s Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau (BCCRB), in cooperation with the New York Urban League, opened a birth control clinic there. (MS to Lasker, July 10, 1939, Mary Lasker Papers, Columbia University, MS Unfilmed )

By the late 1930s, the birth control activists began to focus on high birth rates and poor quality of life in the South, alerted to alarming Southern poverty by a 1938 U.S. National Resource Committee report which asserted that Southern poverty drained resources from other parts of the country. Starting in the mid-1930s, Sanger sent field workers into the rural South to establish birth control services in poor communities and conduct research on cheaper and more effective contraceptive….The birth control movement also looked to Southern states as the ideal region in which to secure funding under New Deal legislation and to establish birth control services as part of state and federal public health programs….

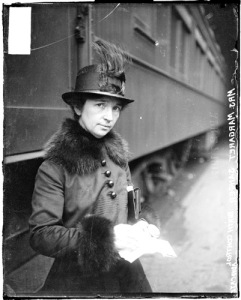

Sanger testifying in Congress, 1934

In 1937, North Carolina became the first state to incorporate birth control services into a statewide public health program, followed by six other southern states. However, these successes were clouded by the failure of birth controllers to overcome segregated health services and improve African-Americans’ access to contraceptives. Hazel Moore, a veteran lobbyist and health administrator, ran a birth control project under Sanger’s direction and found that black women in several Virginia counties were very responsive to birth control education. A 1938 trip to Tennessee further convinced Sanger of the desire of African-Americans in that region to control their fertility and the need for specific programs in birth control education aimed at the black community. (Hazel Moore, “Birth Control for the Negro,” 1937, Sophia Smith Collection, Florence Rose Papers.)

In 1939 Sanger teamed with Mary Woodward Reinhardt, secretary of the newly formed BCFA, to secure a large donor to fund an educational campaign to teach African-American women in the South about contraception. Sanger, Reinhardt and Sanger’s secretary, Florence Rose, drafted a report on “Birth Control and the Negro,” skillfully using language that appealed both to eugenicists fearful of unchecked black fertility and progressives committed to shepherding African-Americans into middle-class culture. The report stated that “[N]egroes present the great problem of the South,” as they are the group with “the greatest economic, health and social problems,” and outlined a practical birth control program geared toward a population characterized as largely illiterate and that “still breed carelessly and disastrously,” a line borrowed from a June 1932 Birth Control Review article by W.E.B. DuBois. Armed with this paper, Reinhardt initiated contact between Sanger and Albert Lasker (soon to be Reinhardt’s husband), who pledged $20,000 starting in Nov. 1939. (“Birth Control and the Negro,” July 1939, Lasker Papers)

However, once funding was secured, the project slipped from Sanger’s hands. She had proposed that the money go to train “an up and doing modern minister, colored, and an up and doing modern colored medical man” at her New York clinic who would then tour “as many Southern cities and organizations and churches and medical societies as they can get before” and “preach and preach and preach!” She believed that after a year of such “educational agitation” the Federation could support a “practical campaign for supplying mothers with contraceptives.” Before going in and establishing clinics, Sanger thought it critical to gain the support and involvement of the African-American community (not just its leaders) and establish a foundation of trust. Her proposal derived from the work of activists in the field, discussions with black leaders and her experience with the New York clinics. Sanger understood the concerns of some within the black community about having Northern whites intervene in the most intimate aspect of their lives. “I do not believe” she warned, “that this project should be directed or run by white medical men. The Federation should direct it with the guidance and assistance of the colored group & perhaps, particularly and specifically formed for the purpose.” To succeed, she wrote, “It takes a very strong heart and an individual well entrenched in the community. . . .” (MS to Gamble, Nov. 26, 1939, and MS to Robert Seibels, Feb. 12, 1940 [MSM S17:514, 891].)

Sanger reiterated the need for black ministers to head up the project in a letter to Clarence Gamble in Dec. 1939, arguing that: “We do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population and the minister is the man who can straighten out that idea if it ever occurs to any of their more rebellious members.” This passage has been repeatedly extracted by Sanger’s detractors as evidence that she led a calculated effort to reduce the black population against their will. From African-American activist Angela Davis on the left to conservative commentator Dinesh D’Souza on the right, this statement alone has condemned Sanger to a perpetual waltz with Hitler and the KKK….The argument that Sanger co-opted black clergy and community leaders to exterminate their own race not only gives Sanger unwarranted credit as a remarkably cunning manipulator, but also suggests that African-Americans were passive receptors of birth control reform, incapable of making their own decisions about family size; and that black leaders were ignorant and gullible.

In the end, Sanger’s plan for an educational campaign to precede the demonstration project lost out to the white medical and public relations men running the new Federation. They were particularly swayed by Robert Seibels (1890-1955), chairman of the Committee on Maternal Welfare of the South Carolina Medical Association, who was chosen by the BCFA to direct a Negro demonstration project in that state. Seibels distrusted Sanger and her loyal crew of field workers, calling them “dried-up female fanatics” who had the gall to tell doctors what to do. (Robert E. Seibels to Frederick C. Holden, Jan. 28, 1939, Sophia Smith Collection, Records of PPFA.) He saw no need for prerequisite education and propaganda and advised incorporating birth control services for blacks into a general public health program. The BCFA then dismissed the notion of building a community-based, black-staffed demonstration clinic that could become permanent, and instead set in motion a plan that closely resembled the vaccination and VD caravans that swept in and out of the region.

Lasker’s money was used to set up demonstration projects between 1940 and 1942 in several rural South Carolina counties, under Seibels’s direction, and in urban Nashville, TN under the auspices of the Nashville City Health Department. In South Carolina, the BCFA hired two African-American nurses to make house calls and meet with women in groups at schools and community centers to encourage them to visit a clinic, but contraceptives were dispensed by white doctors only. In Nashville, demonstration clinics were opened at the Bethlehem Center, a black settlement house, and later at Fisk University, and black nurses were eventually employed with some success there as well.

The Federation immediately claimed that the Negro Project had exceeded its expectations and even persuaded Life Magazine to carry a photo spread of the demonstration clinics in South Carolina May1940. But relatively few women, (only about 3,000) visited the demonstration clinics to receive contraceptive instruction. And among those that did, the dropout rates were high as many women would not return to white doctors for follow-up exams, though the black nurses in both Nashville and South Carolina met with greater success. In 1942 the Federation ended funding for the demonstration clinics claiming to have developed “workable procedures” for providing contraception to African-Americans in both rural and urban communities; but no other clinics appear to have opened as a result of the Project. (“Better Health for 13,000,000,” PPFA Report, April 16, 1943, Rose Papers; John Overton, “A Birth Control Service Among Urban Negroes,” Human Fertility, Aug. 1942, 97-101; Life Magazine, May 6, 1940, pp. 64-68.)

However, the “Division of Negro Service,” a department created at the BCFA initially to oversee the Negro Project, did implement some of the educational goals Sanger outlined. Under the direction of Florence Rose, with money raised by Sanger, and inspired by an advisory council of eminent black leaders, educators and health professionals, the Division undertook significant education projects from 1940-1943. Rose flooded every black organization in the country with planned parenthood literature, set up exhibits, instigated local and national press coverage and hired a black woman doctor, Mae McCarroll, to teach birth control techniques to black doctors and lobby medical groups. Though still stinging from the rejection of her earlier proposal for the Negro Project, Sanger wrote enthusiastically to Albert Lasker in July of 1942 about what she now framed as a pioneering effort: “I believe that the Negro question is coming definitely to the fore in America, not only because of the war, but in anticipation of the place the Negro will occupy after the peace. I think it is magnificent that we are in on the ground floor, helping Negroes to control their birth rate, to reduce their high infant and maternal death rate, to maintain better standards of health and living for those already born, and to create better opportunities for those who will be born. In other words, we’re giving Negroes an opportunity to help themselves, and to rise to their own heights through education and the principles of a democracy.” (MS to Lasker, July 9, 1942, MSM S21:404)

But the BCFA (which changed its name to the Planned Parenthood Federation of America in 1942) forced Florence Rose to leave in 1943 &, a result of her inability to follow new bureaucratic procedures and her allegiance to Sanger, who was immersed in her own clashes with Federation staff. With Rose’s departure, the Division of Negro Service floundered and soon shut down. The Federation delegated “Negro” work to other departments and eventually passed off remnants of the program to state affiliates.

Arguments persist about whether or not the Negro Project was purely a racist endeavor (search for “Sanger” “Negro Project” and “racism” on the Internet and be prepared for the onslaught). Certainly the patriarchal racism of the time that guided many of the social policies in Washington and the practices of philanthropic and charitable organizations working to “lift up” African-Americans, dictated both the Federation’s and Sanger’s approach to blacks and birth control. The public rationale for the Project was rooted in economics, tax-payer burden, and the social threats posed by what was perceived to be an exploding black underclass, rather than the health and sexual liberation of black women (though it should be notes that the birth control movement largely ignored the issue of women’s —black or white— sexual autonomy in the interwar years). And there is no doubt that a good number of medical professionals involved in the birth control movement exhibited strong racist sentiments, some of them arguing for and even carrying out compulsory sterilization on black women considered to be of low intelligence and therefore not capable of choosing not to control their fertility, as well as on those deemed morally or behaviorally deviant. But there is no evidence that Sanger or even the Federation coerced or intended to coerce black women into using birth control. The fundamental belief, underscored at every meeting, mentioned in much of the behind-the-scenes correspondence, and evident in all the printed material put out by the Division of Negro Service, was that uncontrolled fertility presented the greatest burden to the poor, and Southern blacks were among the poorest Americans. In fact, the Negro Project did not differ very much from the earlier birth control campaigns in the rural South designed to test simpler methods on poor, uneducated and mostly white agricultural communities. Following these other efforts in the South, it would have been more racist, in Sanger’s mind, to ignore African-Americans in the South than to fail at trying to raise the health and economic standards of their communities.

Her passion for helping women extended past the realm of birth control. Dr. Stone and her husband, Dr. Abraham Stone counseled couples with relationship and sexual problems from within the clinic as well. This began casually, but it developed into the more formal Marriage Consultation Center which was ran out of the clinic and a community church. Through this work Dr. Stone again acted as a trailblazer, as these marriage counseling sessions had not been done in this manner before. In 1935, Dr. Stone and her husband were able to publish their counseling techniques in a book entitled A Marriage Manual.

Her passion for helping women extended past the realm of birth control. Dr. Stone and her husband, Dr. Abraham Stone counseled couples with relationship and sexual problems from within the clinic as well. This began casually, but it developed into the more formal Marriage Consultation Center which was ran out of the clinic and a community church. Through this work Dr. Stone again acted as a trailblazer, as these marriage counseling sessions had not been done in this manner before. In 1935, Dr. Stone and her husband were able to publish their counseling techniques in a book entitled A Marriage Manual.