Tags

The potential mother is to be shown that maternity need not be slavery but the most effective avenue toward self-development and self-realization. Upon this basis only may we improve the quality of the race.”

(Sanger, “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda,” Birth Control Review, Oct. 1921, 5)

Margaret Sanger’s discussion of dysgenics provides some of the birth control advocate’s most troubling and problematic texts. Her complex perspectives have both frustrated supporters and offered fodder for those seeking to discredit her life’s work. Attempts by those with ideological, political, or other agendas to mislead opponents by avoiding fact and foregoing accuracy are not unique to the current environment. By extracting misleading soundbites from her forays into eugenics, detractors have painted Sanger as a racist and repurposed birth control as a means of controlling minority populations for decades. Manipulating Sanger’s words to support such a claim is historically inaccurate—a gross misuse of quotes without context. However, given the contested nature of the activist’s attempt to wed the function of birth control to the ideology of progressive eugenicists, exploring Sanger’s actual relationship with terms, such as dysgenics and eugenics, presents a valuable learning opportunity.

Before delving into Sanger’s actual views on the subject, it might be useful to first examine the terms dysgenics and eugenics as they were in the early part of the 20th century. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines dysgenics as referring to “Racial degeneration, or its study”—that is the elements that can lead to the deterioration of the human race or subdivisions within it. Eugenics, according to the OED, is the science of selective breeding designed to improve and strengthen the human race biologically, psychologically, behaviorally, etc.

Francis Galton

By the end of the nineteenth century, selective breeding as a means of controlling the country’s genetic destiny and evolutionary tract was gaining popularity as a social and political ideal in America. This movement, most popularly linked to nativist groups, possessed two notable influences. First, the popularity of biological determinism encompasses both dysgenics and eugenics and came on the heels of Charles Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton. Galton has been credited as the father of modern eugenics and for having laid the scientific and ideological groundwork for biological determinism—for many of the selective breeding ideas American eugenicists would eventually trumpet (Selden, Steven, “Transforming Better Babies Into Fitter Families,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 149.2, June 2005, 202).

Then, following Galton’s numerous publications, changes in European emigration patterns began. Americans, who valued Nordic, Germanic, and Anglo-Saxon traits, reacted defensively to new waves of immigrants, who did not possess these traits. In an attempt to both preserve and strengthen the national qualities they valued as “real American,” nativists turned to eugenics. By the early 1920s, as the movement surrounding theories of selective breeding designed to build stronger, healthier Americans had gained notable popularity, applications expanded. No longer did dysgenics and eugenics belong to the American nativists, but to a host of different groups with varying social and political aims (Selden, Steven, “Transforming Better Babies Into Fitter Families,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 149.2, June 2005, 203).

It was in this atmosphere of blossoming enthusiasm that Sanger began to align the functionality of birth control with the ideology of biological determinism. In search of support from respectable professional groups, including eugenicists, Sanger highlighted how contraceptives could be used to pursue “the self direction of human evolution.”

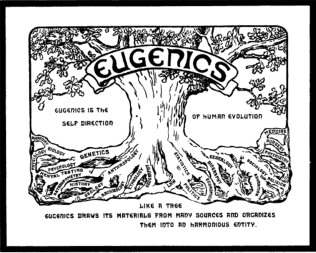

“The Eugenic Tree,” American Philosophical Society, 1932

But, a result of Sanger’s alignment with certain dysgenic and eugenic principles is that her work continues to be challenged even today. Perhaps most deleterious to her character are modern assertions that Sanger was a “racist promoter of genocide.” While Sanger can be considered racist and classist to the extent that many people were during the twentieth century, it is erroneous to overextend that allegation and claim the activist was a proponent of race control (“The Eugenic Tree, Announcements of the Third International Eugenics Congress,” American Philosophical Society, 1932 and Katz, Esther, “The Editor as Public Authority: Interpreting Margaret Sanger,” The Public Historian 17.1, Winter 1995, 44).

Sanger, who aimed to enmesh dysgenics, eugenics, and contraception, was primarily interested in the “racial health” of the human race versus one particular race. What the birth control advocate sought was for contraception to act as a control for the passing of “injurious,” hereditary traits on to future generations. Commenting in 1934 on the German government’s sterilization program, Sanger distinguished which hereditary traits she viewed as injurious and which hereditary traits she did not wish to involve in her eugenic mission:

I admire the courage of a government that takes a stand on sterilization of the unfit and second, my admiration is subject to the interpretation of the word ‘unfit.’ If by ‘unfit’ is meant the physical or mental defects of a human being, that is an admirable gesture, but if ‘unfit’ refers to races or religions, then that is another matter which I frankly deplore.

Sanger rejects race control, but her statement is troubling. Employing birth control and supporting forced sterilization to curtail the reproduction of those with mental or physical challenges causes even her most staunch supporters to raise an eyebrow (Sanger, “Margaret Sanger to Sidney L. Lasell, Jr.,” Feb. 13, 1934).

While unsettling to modern sensibilities, Sanger was not unique in her praise of forced sterilization. As early as 1907, the first compulsory sterilization law was passed in the United States. Specifically, the eugenicist statute passed in the state of Indiana applied to male “criminals, idiots, imbeciles, or rapists.” These groups—“criminals, idiots, imbeciles, or rapists”—coincided with Sanger’s understanding of the unfit. It is important to note that Sanger, along with other eugenicists, believed scientific studies that concluded that those with mental or physical challenges included criminals, alcoholics, drug addicts, etc. and that these groups were incapable of resisting their sexual urges. Her solution at the time, as was the state of Indiana’s solution in 1907, was sterilization. Sanger also considered gender segregation as a possible method for controlling the reproduction of the “unfit.” As science evolved its views, so did Sanger, and after the horrors of World War II, she significantly revised her views of forced sterilization (James B. O’Hara and Sanks, T. Howland, “Eugenic Sterilization,” The Georgetown Law Review 45, 1956, 22)

Beyond compulsory sterilization, Sanger’s alignment with dysgenics and eugenics materialized in her calls for the responsible breeding of the “fit” and the “unfit.” In Sanger’s eyes, “uncontrolled fertility [was] universally correlated with disease, poverty, overcrowding and the transmission of heritable taints”—in so many words, the proliferation of the “unfit.” As a result, she proposed “find[ing] effectual means of controlling & limiting the propagation of the mentally unfit, including feebleminded, psychotic & unstable, mentally retarded individuals.” Worth noting, Sanger specifically meant birth control, not abortion and never infanticide, when she spoke of controlling mentally and physically challenged populations. Her commitment to parents responsibly procreating, via the use of birth control when appropriate, long outlived her tryst with sterilization (Sanger, “The Limitations of Eugenics,” Typed speech, [Sept] 1921, Library of Congress Microfilm, LCM 130:0044 and Sanger, “[Birth Control and Controlling the Unfit Notes],” Autograph draft speech, [1938], Margaret Sanger Papers Microfilm Edition: Sophia Smith Collection, S71:1050).

To summarize Sanger’s relationship with such heated terms as dysgenics and eugenics is a dangerous task. While she married her social mission to that of progressive eugenicists—primarily in an attempt to garner mainstream support for birth control—it is difficult to easily consolidate her beliefs on this complex issue. What we can deduce from the literature she has left behind is that claims of her racism are misguided to say the least and that her dysgenic aims were colorblind. We can also conclude that Sanger understood the eugenic value of contraception to lie in strengthening and empowering the human race. She believed that “the great responsibility of parenthood” was to help diminish the potential of biological weakness in all people, but such beliefs were tempered by the science and the biases of the day. Moreover, these statements are liable to over-simplify perspectives that were more complex in nature and should be taken as the less than exact overviews that they are. Ultimately, Sanger’s campaign for the eugenic benefits of birth control was a divergence from her core mission: that every woman be freed from the shackles of unwanted pregnancy (Sanger, “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda,” Birth Control Review, Oct. 1921, 5).

You say, “Manipulating Sanger’s words to support such a claim is historically inaccurate—a gross misuse of quotes without context.”

Yet, the opening quote is this:

“The potential mother is to be shown that maternity need not be slavery but the most effective avenue toward self-development and self-realization. Upon this basis only may we improve the quality of the race.”

But your opening quote leaves out the context, doesn’t it? Your quote is the third sentence:

“Birth Control propaganda is thus the entering wedge for the Eugenic educator. In answering the needs of these thousands upon thousands of submerged mothers, it is possible to use this interest as the foundation for education in prophylaxis, sexual hygiene, and infant welfare. The potential mother is to be shown that maternity need not be slavery but the most effective avenue toward self-development and self-realization. Upon this basis only may we improve the quality of the race.

As an advocate of Birth Control, I wish to take advantage of the present opportunity to point out that the unbalance between the birth rate of the “unfit” and the “fit”, admittedly the greatest present menace to civilization, can never be rectified by the inauguration of a cradle competition between these two classes. In this matter, the example of the inferior classes, the fertility of the feeble-minded, the mentally defective, the poverty-stricken classes, should not be held up for emulation to the mentally and physically fit though less fertile parents of the educated and well-to-do classes. On the contrary, the most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the over-fertility of the mentally and physically defective.”

I don’t think it does leave out the context, but rather reinforces her point.

“Birth Control will prevent abortion. It will do away with the practice of taking drugs and poisonous nostrums to end undesired pregnancies. It will put an end to the tens of thousands of illegal operations to which women resort in despair. Mothers will not submit to the murder of unborn children when they can control conception.”

—- Sanger Margaret Sanger, “A Better Race Through Birth Control,” Nov 1923.

I’ve always wondered what the reason was that PP began performing abortions given that Sanger said it was the murder of unborn children. I know she died in 1966 and PP started abortions in the early 1970s. Did she change her mind about abortion as she got older? Did she write anything about it? Also, she says in some of her writings that birth control will eliminate abortion. As she got older did she see that it didn’t work?

Any insight would be appreciated!

Thanks!

Tiffany

Planned Parenthood did not offer abortions until they were made legal under Roe v. Wade in 1973. Sanger died 7 years earlier in 1966. In any case, she she had stopped making PPFA policy many years before that. However, though Sanger believed that widespread use of birth control would make abortion irrelevant, she was always opposed to the criminalization of abortion knowing full well that this would lead to dangerous illegal abortions. She also knew that abortion was not something women wanted, so much as it was sometimes necessary.

Thanks! Did she write anything toward the end of her life regarding any of her unrealized assertions about the benefits of widespread birth control?

— abortion becoming irrelevant?

— elimination of prostitution?

— reduction in STDs?

— decrease in poverty?

— eugenics benefits?

Seems like Sanger had a unique opportunity to assess the efficacy of her work over time. I’ve looked for more current writings and I’m not seeing much of her thoughts on the successes or failures.

You might try looking at our digital site, The Published Writings and Speeches of Margaret Sanger, 1911-1959 (http://sangerpapers.org/documents/search.php)

Importantly, Sanger says she deplores sterilization of the unfit if that means members of particular races or religions. Leaving religion to the side for now, it is not a simple matter to decouple concepts of “fitness” and “unfitness” from the (mistaken notion of) biologically defined races that were constitutive of “racial science” discourse at the time. The premise, as explored in SJ Gould’s Mismeasure of Man, et al., was that there were far more “morons,” “idiots,” and “feeble-minded” persons in the, say, “Slavic Race” than the “Nordic Race,” etc. Sanger believed in these unwanted traits were heritable, but the same science that “substantiated” such a claim also taught that intelligence and moral virtues were highly correlated with the supposed hierarchical races. How can she support forced sterilization (pretty grim stuff) of the genetically unfit while “deploring” racial categories that were also based on population genetics and dubious interpretations of evolutionary theory?

Because the charge of racism has dogged her, it would be nice to have a good “go-to” text in which she elaborates on, or clarifies her understanding and use of these murky concepts. As it is, some of her statements appear to be hard to reconcile with others.

A good point. Two books come to mind: Birth Control Politics in the United States, 1916-1945

by Carole R. McCann and Daniel Kevles book, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. You could also take a look at a nice little handout from Reproductive Justice: Expanding Our Social Justice Calling entitled “Margaret Sanger, Birth Control, and the Eugenics Movement.” You can find it at https://www.uua.org/sites/live-new.uua.org/files/documents/washingtonoffice/reproductivejustice/curriculum/4-1.pdf

Thanks for responding. But her praise of the German eugenics program on this page, and her very late endorsement of the Swedish Sterilization Program in 1951 call out for explanation.https://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/webedition/app/documents/show.php?sangerDoc=239501.xml Again, the science she drew on to distinguish “fit” from “unfit” populations is the same science that produced hierarchical scientific racism. The article you provided a link to does not clarify how she interpreted that “science” so as to avoid racism as she claimed to do. If time permits, I will take a look at the books you suggested. But frankly, I find her advocacy of “humanitarian sterilization programs” (see link above) quite troubling, and hard to understand outside of some kind of hierarchical conception of population control for the “betterment of the humanity.” If you have any other thoughts on the matter, I would appreciate hearing them. Otherwise, I’ll try to research the matter (especially her enthusiastic endorsement of the Swedish Program which is now a source of shame in Sweden, see: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1997/08/29/sweden-sterilized-thousands-of-useless-citizens-for-decades/3b9abaac-c2a6-4be9-9b77-a147f5dc841b/?utm_term=.8177dc6a7efa

Until recently I did not know about her interest in such programs, or her praise of German eugenics in 1934. I was somewhat surprised to discover her letters/drafts advocating such things. Thanks again.