Then one stifling mid-July day of 1912 I was summoned to a Grand Street tenement. My patient was a small, slight Russian Jewess, about twenty-eight years old, of the special cast of features to which suffering lends a madonna-like expression. The cramped three-room apartment was in a sorry state of turmoil. Jake Sachs, a truck driver scarcely older than his wife, had come home to find the three children crying and her unconscious from the effects of a self-induced abortion. He had called the nearest doctor, who in turn had sent for me. Jake’s earnings were trifling, and most of them had gone to keep the none-too-strong children clean and properly fed. But his wife’s ingenuity has helped them to save a little, and this he was glad to spend on a nurse rather than have her go to a hospital.

Sanger and the doctor worked for three weeks to fight the septicemia Mrs. Sachs suffered under. Sanger noted that Jake Sachs was kind and thoughtful, and clearly loved his wife and children. When they were about to leave, Sanger reported that “as I was preparing to leave the fragile patient to take up her difficult life once more, she finally voiced her fears, ‘Another baby will finish me, I suppose?’ The doctor admitted the possibility, and noted that she must not try “any more such capers,” or she would die.

“I know, doctor,” she replied timidly, “but,” and she hesitated as though it took all her courage to say it, “what can I do to prevent it?”

The doctor was a kindly man, and he had worked hard to save her, bur such incidents had become so familiar to him that he has long since lost whatever delicacy he might once have had. He laughed good-naturedly. “You want to have your cake and eat it too, do you? Well, it can’t be done.” Then picking up his hat and bag to depart he said, “Tell Jake to sleep on the roof.”

I glanced quickly at Mrs. Sachs. Even through my sudden tears I could see stamped on her face an expression of absolute despair. We simply looked at each other, saying no word until the door had closed behind the doctor. Then she lifted her thin, blue-veined hands and clasped them beseechingly. “He can’t understand. He’s only a man. But you do, don’t you? Please tell me the secret, and I’ll never breathe it to a soul. Please!“

In her memoir, Sanger insisted that she did not know what to tell Sachs, and that in her ignorance she could offer no help. Three months later, the telephone rang and once again Jake Sachs begged her to come to see to his wife. But this time it was different. Sadie Sachs was comatose and died within ten minutes. Sanger walked the city streets, trying but failing to get the images out of her head, images of the poor, the sick, the hungry and those that died. She stayed awake until dawn, and

It was the dawn of a new day in my life also. The doubt and questioning, the experimenting and trying were now to be put behind me. I knew I could not go back merely to keeping people alive. I went to bed, knowing that no matter what it might cost, I was finished with palliatives and superficial cures; I was resolved to seek out the root of the evil, to do something to change the destiny of mothers whose miseries were vast as the sky.

Were Jake and Sadie Sachs real people? Did Sanger change their names in order to protect their privacy? Did the story really happen as Sanger wrote it, or was it fiction or a conglomeration of experiences she encountered in her years as a visiting nurse in the Lower East Side? There is no way to be sure.

What is certain is that Sanger was late in telling the story, especially if it was such a pivotal experience in her life. The first appearance of the story came in 1916, during Sanger’s cross-country speaking tour. In “Woman and Birth Control,” one of her stump speeches, she related the story, noting the Grand Street address but leaving out the names. She indicated that it had happened “three years ago,” in 1913, rather than in 1912. In her 1931 autobiography, My Fight for Birth Control, Sanger spelled the family name Sacks, rather than Sachs, but provided more information about the family. Jake was 32 years old, and their children were ages 5, 3, and 1.

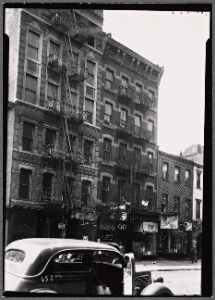

We could not locate the Sachs family in the 1910 census, on Grand Street or anywhere else in Manhattan. But we did locate Jacob and Sarah Sacks, who in 1910 lived on 105 Attorney Street in the Lower East Side, only a few blocks from Grand Street. Both were from Russia, they had three children, Joseph (5), Harry (3), and Dora, who was one and a half. The family does not appear in the 1920 census, with or without Sadie.

We could not locate the Sachs family in the 1910 census, on Grand Street or anywhere else in Manhattan. But we did locate Jacob and Sarah Sacks, who in 1910 lived on 105 Attorney Street in the Lower East Side, only a few blocks from Grand Street. Both were from Russia, they had three children, Joseph (5), Harry (3), and Dora, who was one and a half. The family does not appear in the 1920 census, with or without Sadie.

Terrific and heartbreaking detective story regarding the Sachs family’s existence. Regret to note however that the photo of Grand Street is NOT by Berenice Abbott, but by one of the inspector/cameramen employed by the NYC Tenement House Dept. which collection is in NYPL: http://catalog.nypl.org/record=b19612933~S1. Meanwhile, the tenement interior is by Lewis Wickes Hine, the crusading reform photographer and former Ethical Culture School teacher, whose photographs are also held in NYPL: http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?464294.

Hi Julia, Thanks so much for the comment and for clarifying the photo citations. I have linked the interior image to the NYPL’s digital gallery and corrected the captions. –

Pingback: What Have You Done This Month? « Margaret Sanger Papers Project Research Annex

This was really scary and the need for better doctors and knowledge in the life of a woman.

Pingback: Planned Parenthood at 100: Birth Control Changed Everything

Pingback: How Planned Parenthood Changed Everything | Nigeria Newsstand

Pingback: 100 yrs ago, Sunday: Oct. 16, 1916: My preface, plus “How Planned Parenthood Changed Everything”, from TIME.com | ThinkWing Radio with Mike Honig

Pingback: Margaret Sanger, la lactancia materna y la ciudad | Las Interferencias